A (heavily edited) German version of this article has been published in iX 10/2024.

Table of Contents

Abstract

Introduction

AsciiDoc as a Lightweight Markup Language

Showcase: What Antora Looks Like

Getting Started with the Eclipse Jetty Example

Docs as Code Par Excellence: What Antora Has to Offer

More Than Just Gimmicks: The Playbook

Working with the Content

Nothing Lasts Forever: Versioning Documentation Correctly

Names and Versions Combined: Component Versions

Everything in Its Place: The Antora Directory Structure

Linking with Resource IDs

Completing the Picture: Adding Custom Images and Kroki Diagrams

Conclusion

References

Jetty Links

Abstract

AsciiDoc is excellent for individual documents. However, it becomes more challenging when entire documentation needs to be consistently structured and maintained across multiple repositories. That’s exactly what Antora is for: a documentation generator for static websites whose content is based on AsciiDoc.

Introduction

Software documentation is important—despite all the lazy excuses. Lightweight markup languages and Docs as Code approaches are indispensable when it comes to sustainably documenting the various abstraction layers of a software architecture.

Classic markup languages, such as HTML or LaTeX, do have the advantage that, unlike binary formats like those produced by office programs, they reveal all “settings” and “parameters” and thus are visible to the human eye. However, they also have the disadvantage of often being quite difficult to read and even more difficult to write.

This is where so-called lightweight markup languages come in. They are characterized by simpler syntax that doesn’t interrupt the writing and reading flow. The best-known example is Markdown, but also the world-famous Wikipedia uses a lightweight markup language (MediaWiki), as does Jira (Jira Formatting Notation).

The English Wikipedia now lists over 20 lightweight markup languages. In [Hei23], I compared them with the aim of finding not just a language for software developers but one for everyone. Anyone still looking for (undeniable) arguments for the necessity of software documentation can find them in [Hei22]. Both articles are available for direct viewing (in English) and downloading (in German).

AsciiDoc as a Lightweight Markup Language

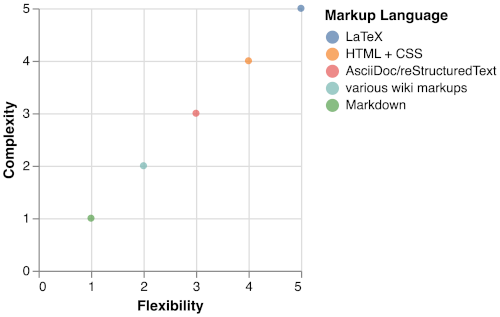

The more flexible a markup language is, the more complex it becomes, as qualitatively shown in the diagram below. With Markdown at the lower end (very limited functionality but very simple) and LaTeX at the upper end of the scale (virtually unlimited functionality but relatively cumbersome), AsciiDoc and reStructuredText emerge as the perfect compromise candidates.

While AsciiDoc meets all the requirements of a general-purpose lightweight markup language, reStructuredText is more at home in the Python world. As a language and with its standard documentation generator Sphinx [Sph] (essentially the counterpart to Antora for AsciiDoc), it is noticeably more geared toward “techies.”

Docs as Code means that documentation is treated like source code. The most important prerequisite for this—namely a text format instead of a binary format—is already fulfilled with AsciiDoc as a lightweight markup language. To edit AsciiDoc documents, the same integrated development environment (IDE), the same version control, the same integration into organizational and technical processes, and the same CI/CD pipeline as for the actual program code can (and should) be used.

For the most common IDEs, there is the AsciiDoc plugin (for JetBrains IDEs and Visual Studio Code) or the Asciidoctor Editor (for Eclipse). For browsers, the Asciidoctor.js Live Preview plugin is recommended. GitHub and GitLab can render AsciiDoc documents directly.

The standard generator for individual AsciiDoc documents is called Asciidoctor [AscDr]. This also represents the reference implementation of the AsciiDoc language and hosts the official language documentation [AscDocLanDoc]. Anyone wanting to learn AsciiDoc—for which there is unfortunately not enough space in this article—should therefore always consult Asciidoctor and not the original AsciiDoc sources. Probably the most concise introduction to AsciiDoc can be found on the Antora website [AntAscDocPri].

Showcase: What Antora Looks Like

Antora provides—although hidden behind a rather unassuming “ticket”—a collection of projects that use Antora to generate their documentation [AntSho]. As everywhere, you’ll find the full spectrum in terms of content, appearance, and quality. If you want to see particularly well-designed Antora documentation (many of which have their own UI), the following projects are recommended for viewing, all of which rank fairly high in the list:

- Couchbase

- Neo4j

- Spring Security

- Open Liberty

- Apache Camel

You can also try out how different versions can be selected in the showcased projects—not everywhere, but at least in some sections of the respective documentation.

Antora uses Node.js as its runtime environment [AntRunQui]. To minimize local installations and keep your own system clean, however, in this article it will always be run as a Docker container.

How Antora is set up with Docker is officially described in [AntRunCon]. There, however, you will often find long and unwieldy command-line prompts. In addition, it makes sense to install Kroki right away as a local diagram generator. What Kroki diagrams are all about is explained in the second-to-last section.

As an add-on to this article, I therefore provide you with both a custom-tailored Dockerfile (antora_with_kroki_extension.Dockerfile) and a custom-tailored Compose file (compose_antora_with_kroki.yaml) [DocMinPro]. All explanations in this article refer to this Docker configuration, which you are of course welcome to use for your own Antora projects. I would, however, appreciate attribution and reference.

Getting Started with the Eclipse Jetty Example

Of course, it is possible to set up an Antora project from scratch, but within the scope of an article this is neither didactically useful nor practical for demonstrating the concepts. Therefore, I selected a representative open-source project from the showcase in the previous section on which all the steps can be directly illustrated.

The choice fell on Eclipse Jetty [EclJet]. Jetty is a Java web server and servlet container, maintained by the Eclipse Foundation, and it can be used both privately and commercially under either the EPL-2.0 or the Apache-2.0 license [EclJetLic]. Its documentation—and only this is relevant here—includes both local and external content sources, contains multiple versions, generates diagrams from code, uses a custom UI (although UIs are not covered in this article), requires very few plugins, and can be generated with relatively little effort.

The following step-by-step guide explains how to generate the Jetty documentation with Antora for the first time, using the accompanying Docker configuration.

-

First, clone the GitHub project of the Jetty website into the local folder jetty_site:

git clone https://github.com/jetty/jetty.website jetty_site -

Then change into the newly created directory; from now on, it will serve as the working directory for all upcoming steps.

cd jetty_site -

Reset the local repository to the state before August 8, 2024:

git reset --hard 8975f7fYou should then see the message

HEAD is now at 8975f7f add slack notification.(Background: In August 2024, plugins were added to the Antora documentation project that significantly complicate generating the documentation locally in a clear, didactic manner.)

-

Copy the two provided Docker files

- antora_with_kroki_extension.Dockerfile and

- compose_antora_with_kroki.yaml

into the jetty_site directory.

-

If you are working on Windows:

Replace the three occurrences of

$PWDin the file compose_antora_with_kroki.yaml with the absolute path of your local Jetty directory, though in two different notations. If your checked-out Jetty repository is located, e.g., at C:\Projects\jetty_site, then-

replace the first

$PWDwithC:/Projects/jetty_site(using/instead of\), -

replace the second and third

$PWDwith/c/projects/jetty_site(using/cinstead ofC:), -

remove the

:Z, and -

enclose the line under

volumes:in quotation marks.

The compose file should therefore look like this in the relevant section:

volumes: - "C:/Projects/jetty_site:/c/Projects/jetty_site" working_dir: /c/Projects/jetty_site -

-

The following command downloads the Antora and Kroki images (for the first time), starts the local Kroki server, runs the Antora generator based on the playbook antora-playbook.yml, and shuts down the Kroki server again once Antora is finished:

docker compose -f compose_antora_with_kroki.yaml up --abort-on-container-exitThe first run may take about two minutes depending on your internet speed. The message

pull access denied for antora_with_kroki_extension, repository does not exist or may require 'docker login'simply means that the image is not yet available locally (and is therefore being downloaded). -

The generated documentation can then be viewed in the web browser at [local]/jetty_site/target/site/index.html.

With every change to the Antora configuration or the content, step 6 must be executed again. It is recommended to delete the local output directory target beforehand each time.

To finally remove the containers from the Docker list, the following command is sufficient:

docker compose -f compose_antora_with_kroki.yaml downDocs as Code Par Excellence: What Antora Has to Offer

Antora collects AsciiDoc files and resources, such as images or code snippets, from one or more local and external Git repositories and generates static HTML pages from them.

Following the DRY principle (“Don’t Repeat Yourself”), Antora allows the reuse of resources, such as code snippets (even directly from the original source code), or elements that need to appear in multiple documents, such as copyrights, disclaimers, or references.

The focus on Git repositories plays to the strengths of developers. Documentation should be located close to the actual source code, and today that is almost always in Git, whether on GitHub, GitLab, Bitbucket, or in a local repository.

The artifacts produced by the Antora generator are purely static websites. They can be viewed offline, uploaded to any web host, or moved between hosts. Since they are independent of content management systems (CMS), both vendor lock-in and the typical security risks of such systems are avoided.

With templates and UIs, websites can be designed consistently and—after a certain initial effort—adapted to a company’s corporate design. Antora already provides a fully functional standard UI, which may not win a design award but more than fulfills its purpose.

Regardless of where the data comes from or where the generated websites are exported to, the linking of resources always follows a platform-independent scheme. After a migration, authors therefore don’t have to deal with inconsistent links, relative paths, or broken references. Antora has its own internal “coordinate system.”

Just as the software being documented has different versions, the corresponding Antora documentation can also contain multiple versions. The appropriate software—and thus documentation—version can easily be selected from a dropdown menu on the website.

Navigation structures on the left side can also be easily implemented using AsciiDoc lists and the references they contain.

More Than Just Gimmicks: The Playbook

For Antora to know what it should do, it first refers to the playbook—a simple configuration file usually written in YAML syntax. The common, though not mandatory, filename is antora-playbook.yml.

The playbook defines, among other things, the following information, many of which are optional:

- global properties such as the title, base URL, or start page of the generated documentation

- which local and external repositories, branches, and tags serve as content sources

- Asciidoctor extensions and AsciiDoc attributes

- the UI bundle to be used, including layout, style, and page behavior

- target location and format of the published pages

- how Antora handles repository updates and its cache

In short: the playbook defines which sources Antora should use, which settings it should apply, and where the finished documentation should be generated.

Some playbook entries are best explained directly in Jetty’s antora-playbook.yml. This file is located in the root directory jetty_site of the Git repository cloned earlier.

site:

title: Eclipse Jetty

url: https://jetty.org

keys:

google_analytics: G-VS4ZRD6HVM- Only

titleis mandatory. urlspecifies where the documentation can be accessed once it has been published. It must always be provided—even for possible subdirectories—without a trailing slash/.keyscontains various key-value pairs for services, UI, templates, and extensions, with this example showing only one for Google Analytics.start_page(not present in the example) specifies the Resource ID of the start page. How such an ID is structured will be explained further below. If the start page is located atROOT:index.adoc, its explicit specification can be omitted—as is the case here.robots(also not present here) can contain instructions such asallowordisallowfor search engines, similar to the well-knownrobots.txtfile.

Working with the Content

Antora collects the content, i.e., the actual material, from all the local and external Git repositories specified in the playbook. For Antora to actually process the content, there must be a file named antora.yml and a specific directory structure in addition to the exact location (Content Source Root). How exactly these two must look will be explained in the following sections.

content:

sources:

- url: .

branches: HEAD

start_paths: [home, docs-home, contribution-guide]

- url: https://github.com/jetty/jetty.project

branches: jetty-{12,11,10}.0.x

start_path: documentation/jettyIn the Jetty playbook, essentially two content sources are defined. Each source, whether local or external, must always be a Git repository.

- The upper

urlsource refers to the local directory.(i.e., jetty_site). Withbranches, the branch of the GitHEAD(i.e.,main) is specified. Here the three localstart_pathshome,docs-home, andcontribution-guideare of interest. The documentation (apart from the following, more extensive external part) is assembled from these three local parts [JL1], [JL2], and [JL3]. More specific local path specifications must always begin with./if they are given relative to the location of the playbook (and not to the current working directory). - The lower

urlsource refers to the external repository github.com/jetty/jetty.project. To avoid any confusion: when cloning the entire Jetty documentation project a few sections earlier, the repository github.com/jetty/jetty.website was used, not […]/jetty.project. jetty.website uses sources from jetty.project for its documentation. The latter also contains the actual Jetty program code. The documentation is located—in line with the Docs as Code approach—in proximity to the code, namely in the subdirectorydocumentation/jettyreferenced bystart_path. Since separate documentation should be generated for each of versions 12, 11, and 10, the three relevantbranchesare listed in short form (jetty-12.0.x,jetty-11.0.x,jetty-10.0.x) [JL4][JL5][JL6].

output:

dir: target/site- The specification of the output directory with

diris self-explanatory. - With

clean: true(not present here), the directory can be automatically deleted before regeneration. However, this option should only be used with caution.

Nothing Lasts Forever: Versioning Documentation Correctly

Authors should maintain each documentation version (Component Version) in Git in its own branch (the branches key in the playbook), not with tags. At first glance, this may seem contradictory, since software versions are usually marked with tags. However, documentation must remain editable even after the release and thus “freezing” of the software version—whether for typos, new chapters, or later insights. Often the documentation is not yet fully updated at the time of a release anyway. With tags, it would remain frozen.

Antora does support tags in the playbook. Those who still want to use them should employ dedicated tags independent of software releases, such as docs/1.3.9 instead of release/1.3.9. This way, there is at least a grace period after the software release to complete the documentation, since—as is well known—the two are rarely finished at the same time.

Alternatively, Antora can work with separate version directories (the start_paths key in the playbook), meaning one directory per documentation version. The actual version is then specified in the Component Version Descriptor (antora.yml). More details on this will follow in the section after next.

Names and Versions Combined: Component Versions

Jetty’s playbook refers, among other things, to the large external branch [JL4]. The antora.yml file contained in the Content Source Root begins as follows:

name: jetty

version: '12'

title: Eclipse Jettytitleis optional but recommended. It appears in the title of the generated HTML pages.nameandversiontogether define a Component Version. Antora consolidates all resources with the same name and version, meaning a Component Version can also consist of multiple sources, each containing its own antora.yml file. As long asnameandversionare identical, they are considered one and the same. Issues arise only if settings within them conflict or source files collide.

Because it is always the antora.yml file that defines the name and version of a component (and not the playbook, a directory name, or the version number of a Git branch), it is referred to as the Component Version Descriptor.

In the Component Version Descriptor of the external branch for version 11 [JL5], version: '11' appears with the same component name: jetty.

If no versions are to be used for a component—which may make sense for something like an employee handbook—then the reserved value ~ must be set (i.e., version: ~).

A Component Version Descriptor may also contain additional entries, as seen in Jetty’s external branch, such as AsciiDoc attributes (asciidoc.attributes:), navigation (nav:), or configurations for plugins and extensions (ext:). However, these will not be discussed here.

Optionally, you can specify a start_page, as long as it is not index.adoc.

Everything in Its Place: The Antora Directory Structure

Each Content Source Root, i.e., each location declared as content in the playbook, must follow a specific directory structure:

[Content Source Root] ➊ │ ├── antora.yml ➋ │ └── modules ➌ │ └── ROOT ➍ │ └── pages ➎ │ └── source_file.adoc

➊ The root of a repository automatically forms a Content Source Root, unless another root (i.e., a subdirectory of the respective repository) is specified in the playbook with start_path or start_paths.

➋ Every Content Source Root must at the top level contain a file named antora.yml, which serves as the Component Version Descriptor (see previous section).

➌ Every Content Source Root must also at the top level (and thus parallel to the antora.yml descriptor file) contain a directory named modules. This modules “container directory” must contain at least one module (i.e., at least one module subdirectory).

➍ It is recommended to use a module named ROOT because it has some special properties, particularly with regard to the start page and linking. You can think of ROOT as an alias for an empty module name.

For small documentation projects, a single module (ROOT) is likely sufficient, whereas larger projects (such as Jetty) can consist of additional modules. In Jetty’s case, these are operations-guide [JL7], programming-guide [JL8], and code, the latter containing only source code snippets (examples) that are included in the pages of other modules.

A module directory must contain at least one family subdirectory.

➎ A family can be understood as the “type” of a resource. The name of the directory determines the family of the files (resources) it contains.

pages: AsciiDoc files (with the .adoc extension) from which HTML pages are generatedpartials: typically, but not necessarily, AsciiDoc files whose contents (“snippets”) are included in other AsciiDoc files, such as common descriptions, terminology, or reference tablesexamples: source code, terminal output, datasets, log entries, or other non-AsciiDoc files that are inserted, wholly or in part, into pagesimages: image files in .png, .jpg, .svg, or .gif formats, embedded as images in pagesattachments: downloadable files such as .pdf or .zip that are usually referenced in AsciiDoc usingxref:

Antora also supports symbolic links, such that, e.g., the examples family directory can directly reference the source code (often a src directory) of a software project.

Navigation files (nav.adoc) are not covered here. In the Jetty example project, however, it is apparent that they mainly consist of lists with cross-references (xref:).

Linking with Resource IDs

Antora automatically assigns a Resource ID to every resource, i.e., every file located in a valid family directory. This ID can be uniquely constructed and reconstructed, making it completely independent of file systems, relative path starting points, URLs, or even whether the resource is stored locally or externally. Resource IDs can be used in AsciiDoc pages everywhere files are referenced—most notably in xref: and image: macros or in include:: directives.

A Resource ID consists of five coordinates, though in practice not all five need to be specified:

version@component:module:family$fileversion@: Specifies the version of the target resource’s component and must always end with@. If omitted, the latest Component Version is used.component:: Specifies the name of the target resource’s component and must always end with:. If omitted, the current component is used.module:: Same idea, but for the module. TheROOTmodule can be specified as a kind of “nameless” module with a standalone colon:.family$: Specifies the name of the family directory, without the pluralsbut with a trailing$, e.g.,page$,partial$,example$,image$, orattachment$. Forimage$andpage$targets, the family can be omitted—except when embedding images via thexref:macro. In all other cases, the family must be specified.file: Contains the path or filename of the resource and is always interpreted relative to the family directory.

In the Jetty example project, you’ll find many cross-references (sometimes very simple ones) using Resource IDs, such as [JL9] (linking to other documents in the same module), [JL10] (embedding an image from the same module—with no need to specify the image$), or [JL11] (including a code snippet from a Java file in another module). The corresponding references are shown with highlighting in the following listing:

[JL9] xref:protocols/index.adoc#http3[Configure HTTP/3]

[JL10] image::jmc-server-dump.png[]

[JL11] include::code:example$src/main/java/org/eclipse/jetty/docs/programming/client/ClientConnectorDocs.java[tags=typical]Completing the Picture: Adding Custom Images and Kroki Diagrams

The Antora documentation for Eclipse Jetty includes both local and external content. Local pages are particularly convenient for making quick custom adjustments.

In the previous section, embedding an image didn’t look particularly impressive because the image was included from the same module as the page itself. Slightly more interesting is embedding the same image (namely jmc-server-dump.png) in the local documentation home page [JL12]. There, it must be inserted below image::jetty-logo.svg[…] (i.e., after line 3):

image::jetty:operations-guide:image$jmc-server-dump.png[alt=JMC Server Dump,width=50%]This insertion links from the local component ROOT to the external component jetty and then into the module operations-guide. Since this is a “regular” image inclusion, the family specification image$—as mentioned in the previous section—is optional, meaning the following variant works just as well:

image::jetty:operations-guide:jmc-server-dump.png[alt=JMC Server Dump,width=50%]Finally, let’s see how text-based diagrams—also called Diagrams as Code—can be rendered with Antora.

There is a wide range of diagram types that can be described textually in AsciiDoc. Kroki provides a unified API and a web service to render these diagrams efficiently. Those who (understandably) prefer not to have their diagrams rendered externally can also use a local Kroki installation.

A picture is worth a thousand words, and 30 pictures are worth 30,000 words, which is why we’ll skip further explanation and instead refer you directly to Kroki’s extensive example collection, which is well worth exploring [KroExa].

The Docker files provided at [DocMinPro] install the asciidoctor-kroki extension for Asciidoctor (which is used by Antora as its processor) in the […].Dockerfile and start a local Kroki server in the compose_[…].yaml, allowing diagrams to be rendered locally without accessing the kroki.io server. Both Docker files are thoroughly documented.

By default, Jetty’s documentation already contains around 30 textually encoded diagrams. Up until now, however, they haven’t been rendered because the corresponding extension was not yet activated.

To change this, add the following key-value pairs in the asciidoc block (not the antora block!) in the antora-playbook.yml under attributes:

kroki-server-url: http://kroki:8000

kroki-fetch-diagram: trueAnd under extensions, add the list entry:

- asciidoctor-krokiThe following listing summarizes this section with the necessary adjustments:

asciidoc:

attributes:

experimental: ''

idprefix: ''

idseparator: '-'

page-pagination: ''

kroki-server-url: http://kroki:8000

kroki-fetch-diagram: true

extensions:

- ./lib/feed-block-macro.js

- ./lib/javadoc-block-macro.js

- ./lib/jetty-block.js

- ./lib/skip-include-processor.js

- ./lib/absolute-path-include-processor.js

- asciidoctor-krokiYou may have noticed that the Jetty playbook already provides an option in the antora section to register the asciidoctor-kroki extension by setting enabled: true. Jetty also supplies its own JavaScript file for the extension. However, if you want to use your own local Kroki server instead of the external kroki.io server, you still need to add the two kroki- attributes shown above. For custom Kroki projects unrelated to Jetty, the originally described method using the two Docker files and the playbook adjustments is usually simpler and more flexible.

Once the documentation is regenerated after the mentioned adjustments (where it is recommended to always delete the entire target directory beforehand), the whole process takes about a minute longer because several diagrams are newly created. Under [JL13] and [JL14] you’ll find two pages of the documentation that each showcase a series of such diagrams.

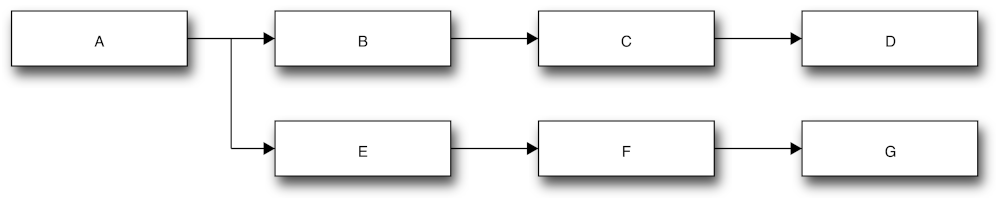

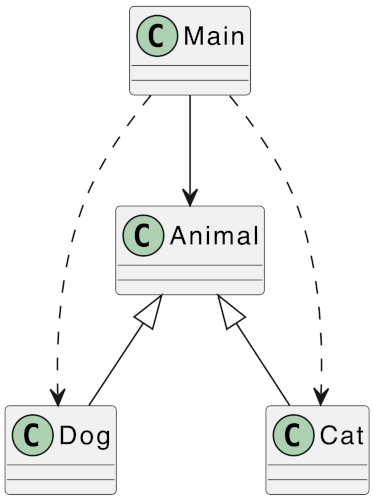

The demonstrated diagrams are fairly extensive and cannot easily be edited since their code resides in an external repository. It’s more interesting anyway to create your own diagrams “from scratch” to experience firsthand the simplicity and efficiency of Diagrams as Code. The following two listings contain a block diagram and a UML class diagram, which you can add directly to the local documentation home page from the beginning of section [JL12]. After running Antora again, the two diagrams will appear on the local Jetty start page in the browser.

[blockdiag,width=500px]

....

blockdiag {

A -> B -> C -> D;

A -> E -> F -> G;

}

....

[plantuml,height=500px]

....

class Animal

class Dog

class Cat

class Main

Animal <|-- Dog

Animal <|-- Cat

Main --> Animal

Main ..> Dog

Main ..> Cat

....

Conclusion

With the concepts presented here—and perhaps a bit unfamiliar at first—the path is now clear for your first documentation project with Antora. To make getting started even easier, I provide an Antora minimal project for download at [DocMinPro]. Before first use, it only needs to be converted into a local Git repository. A short guide on how to do this is included there as well.

References

- [AntAscDocPri]

- Antora AsciiDoc Primer, docs.antora.org/antora/latest/asciidoc/asciidoc/

- [AntRunCon]

- Antora Run in a Container, docs.antora.org/antora/latest/antora-container/

- [AntRunQui]

- Antora Install and Run Quickstart, docs.antora.org/antora/latest/install-and-run-quickstart/

- [AntSho]

- Antora Sites Showcase, gitlab.com/antora/antora.org/-/issues/20

- [AscDocLanDoc]

- AsciiDoc Language Documentation, docs.asciidoctor.org/asciidoc/latest/

- [AscDr]

- Asciidoctor, asciidoctor.org

- [DocMinPro]

- Docker Files and Minimal Project for Antora, link.simplexacode.ch/8xdv

- [EclJet]

- Eclipse Jetty, jetty.org

- [EclJetLic]

- Eclipse Jetty License, github.com/jetty/jetty.project/blob/jetty-12.0.x/LICENSE

- [Hei22]

- C. Heitzmann, Javadoc with Style, link.simplexacode.ch/gh32

- [Hei23]

- C. Heitzmann, Markup Languages in Software Documentation, link.simplexacode.ch/4gwr

- [KroExa]

- Kroki Examples, kroki.io/examples.html

- [Sph]

- Sphinx, www.sphinx-doc.org

Jetty Links

Shortlink to this blog post: link.simplexacode.ch/g7qi2025.12